Scott Rossi

Can you introduce yourself, what was your trajectory until picking up a camera? How did photography enhance your ability to communicate?

I grew up in the suburbs of Vancouver, B.C. When I was 5 years old, my father arrived home with a go-kart. I had no idea the impact this would have on my life. I spent the next thirteen years racing go-karts professionally around the world, from British Columbia to the streets of Monte Carlo.

I only started taking photographs in my last year of university, pretty much by accident. I had to choose an elective so I could graduate, I remember choosing photography class over ceramics. My professor there introduced me to Garry Winogrand’s and Joel Meyerowitz’s work. I got into street photography for a while and spent the next two years photographing my surroundings, but without much intent behind it. Soon, I began to feel detached from the practice altogether and that street photography lacked a connection to the subjects I was photographing.

It was at this point that I began to pursue long-form projects. In them, I discovered the power of visual storytelling. I began to value not just the results, but the process of engaging with my subjects, establishing an intent to the work that previously lacked.

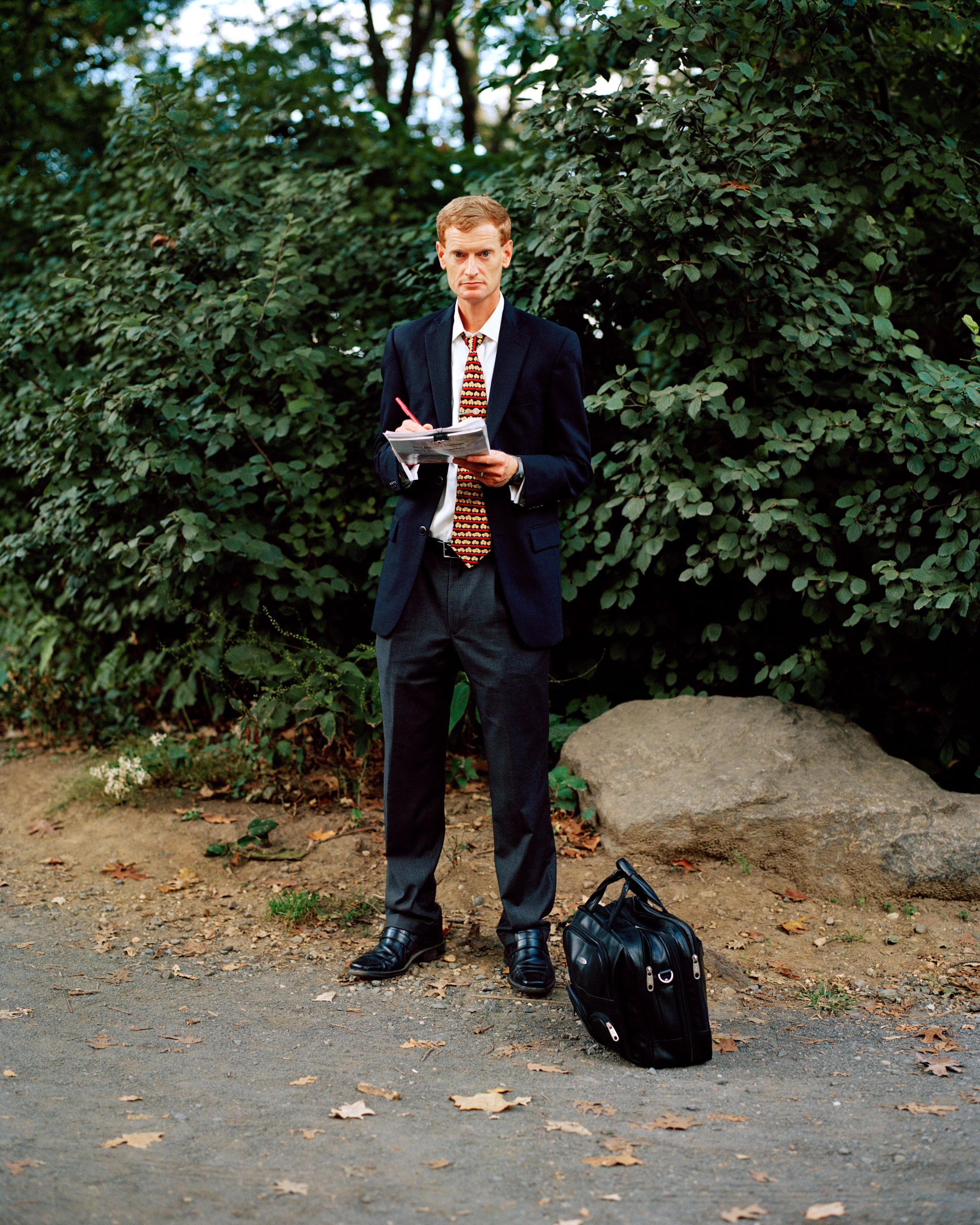

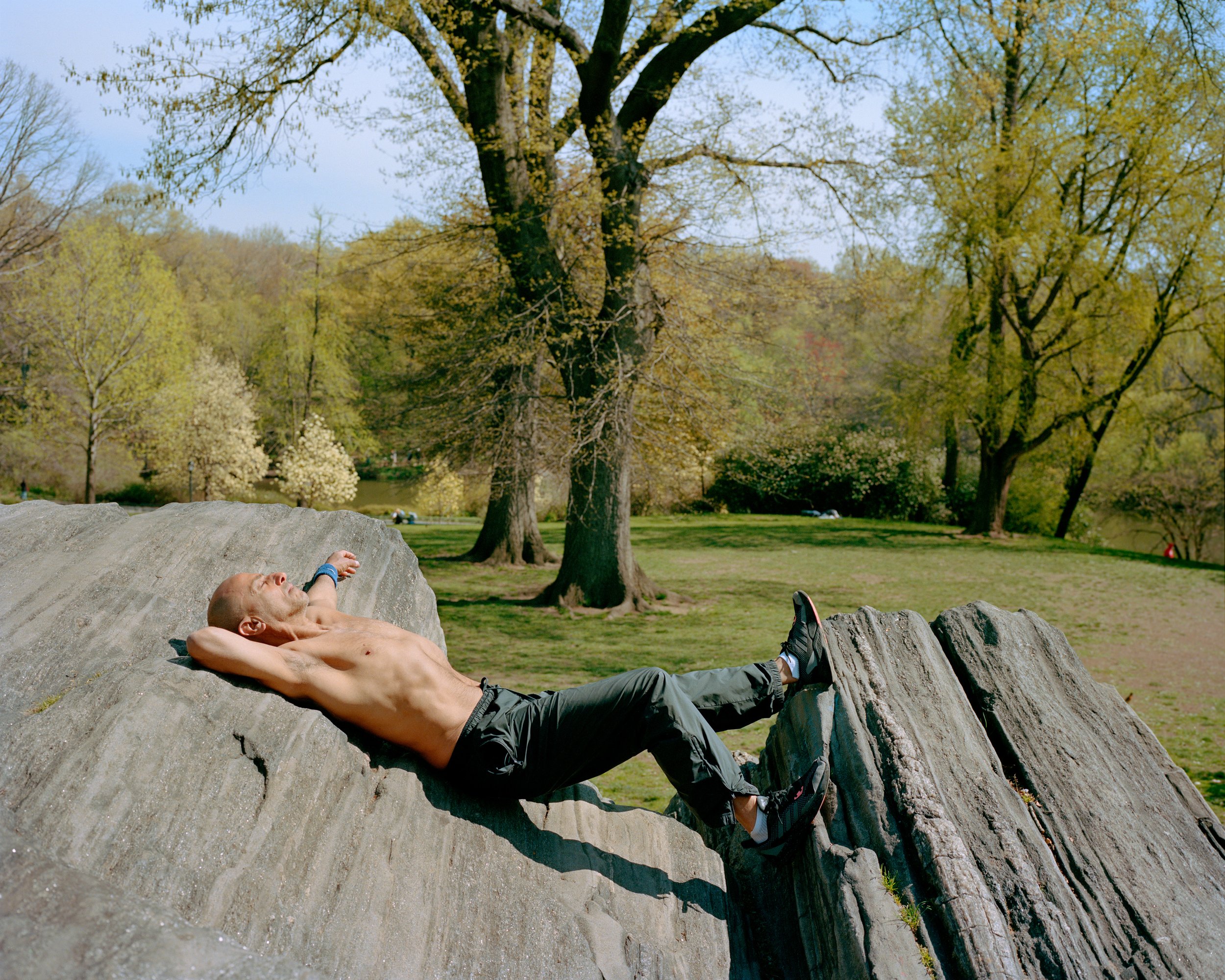

The first two projects I worked on, Burned Out (2018-19) and Jazz House (2018-20), I documented coming-of-age stories, while drawing from my own experiences. Whereas Common Place (2021), which I began shortly after moving to New York City while studying at ICP, explores the history of Central Park and the relationship between New Yorkers and the public space in the context of a global pandemic.

The project explores the results of intentions set forth by the park's chief architect, Frederick L. Olmsted, who wanted Central Park to be a democratic space that allows all New Yorkers to escape from the distractions of urban life in Manhattan. Olmsted believed that, by recreating the peacefulness of nature, parks would soothe and restore the human spirit. Never has Olmsted's vision been more relevant than during this global crisis, which has taken millions of lives while stay-at-home regulations swept across the globe. Whether using the expansive landscape as a place to relax, to escape or to love, this project translates these actions photographically. Common Place illustrates the importance of public parks and how during this moment, New Yorkers found what they needed within Central Park

In your series Common Place how did observing / people watching help you create a narrative throughout this series?

All my work is driven by curiosity. While I am walking around, certain things pique my interest and draw me in-– the way someone is holding their partner, or the way the light hits a certain tree trunk. The narrative of the project definitely came from observing these things. I never went out with an agenda or shot list. I tried to follow my intuition and later, when I had the photos in front of me, I let them speak to each other and soon enough a narrative began to appear. This is the approach I take with all my projects.

The hardest thing is to trust my instinct and not talk myself out of approaching someone or going in a particular direction. Besides this, I also used poetry to help guide me through the creative process. I wrote a lot trying to understand the more internal narrative of the project as well, the one that concerns how I felt while photographing.

Can you share the internal dialogue that occurs when talking yourself into approaching someone rather than choosing not to? Also, how has documenting your process helped in future situations?

Honestly, I probably look very strange standing in the open talking to myself. I often wonder if the debate is strictly internal, or if you can see it on my face.

Typically, it’s just nerves holding me back. I’m nervous they will say no, or be rude to me, or I will embarrass myself. Sometimes I try to convince myself it’s not worth photographing to avoid this anxiety, but most of the time I am able to overcome my nerves and approach people. In the end, the worst thing that could happen is the person saying “no.”

Keeping notes and writing about my experience of photographing always inform future practice. It is only natural.

How do you build trust with those you approach and photograph? How do you

engage them in conversation (what might you say as your introduction to your

desire to photograph them?)

It really depends on the person I am approaching. Some people want to talk and get to know each other, while others want me to take the picture and leave. It’s hard to put into words, but I can often tell whether the person wants to talk or not when I introduce myself. But my initial approach is almost always the same, with some variations in language: I approach with a smile, my camera over my shoulder and explain who I am and what I would like to do with them. I make a point of always being up front and open about what I intend to do with the work and get their contact information to share the picture with them.

I don’t fully understand how I get the trust of total strangers so quickly. It can be hard to gain the trust of people I know intimately let alone a stranger who I intend to photograph. I don’t do or say anything that is particularly striking. I’m just myself. And of course, the photographs don’t always turn out, but I will have made that connection with someone which is a truly rewarding experience.

For the couples you have photographed for this series/? How have you been able to photograph them in such intimate ways? What direction might you give them to help them achieve these comfortable postures and poses in front of your camera?

Many of the couples I photographed were as they are in the photos when I approached them. I guess my method was to seek out people in states of comfort or moments of intimacy. It was a little awkward to interrupt some of them, but I was always transparent about what I was doing and would talk to them quite a bit before taking any pictures. We would talk about their relationship, the part of the park they were in, and their relationship with the park. I would try to get to know them in our short time together, and share a lot about myself, which I think helped them remain relaxed, as well.

I found that when people were already comfortable, there was not much direction to give them. Most of my direction was about their glance, whether to look at the camera or not.

How has studying the park as a public space demonstrated the way open spaces act as a method of therapy, did this come up in your discussions with those you photographed?

Personally, I have always sought public spaces as a method of therapy. In New York, it’s the best way for me to grapple with my thoughts and anxiety.

A lot of people I meet speak to me about memories from their youth or previous visits to New York and Central Park that shaped their experiences of the city. Many referred to its calming, peaceful environment as a source of therapeutic healing. A few people I met had a deeper relationship with the space, as well.

Late in the summer, for example, I met a man named Dave. Dave was on a rock in the Ramble holding his hands up toward the sky when I introduced myself. He told me that he visits this rock almost every day. He calls the rock “Mothers Rock” because it is the exact location where he was when he found out his mother passed away six months before. Whenever he visits the rock, he holds his hands up to the north, east, south, and west, whispering messages to his mother while he does it.

This is one of many people who had a deep relationship with the space, for one reason or another.

To keep up to date with Scott Rossi’s latest work follow along here:

Website

Instagram