Robin Bernstein

Can you introduce yourself? Where are you based, what inspired you to communicate through photography?

Primarily photography has always been a way of engaging with the world around me. My fascination with pictures began when I was a child — I would engross myself in the pages of TIME and National Geographic, as well as those big history picture books with titles like “Illustrated History of the World” and “1000 Years in Pictures”. It’s hard to pinpoint what sparked my initial interest in the act of taking pictures — it probably came about during a period of my life where I was traveling. It started to make sense to me to use the camera in that cliché way of gaining access and documenting my experience within various spaces. Early on I started to understand the serious weight that the act of making images, and the images themselves could carry — even my travel snaps from my early days of using a camera tended to have a focus on some of the same themes which still carry through in my work today — change and decay within urban space, signifiers of spatial division, and a focus on how people negotiate their environment.

Secondly, the technical aspect of the camera as a tool was and still is a big draw for me — I have a deep love for more mechanical and analogue equipment and enjoy the tactility and striving to understand how it functions.

I recently relocated from Cape Town to London, where I am currently based.

From your website I came across this: My work is made in the context of interactions that I have with my subjects, and in turn the interactions that we both have with the environment we find ourselves in. The environment — be it ‘natural’ or built — is viewed as the embodiment of a constant negotiation between those who inhabit the land and the land itself.

Can you share how the land itself is an important part of your work? How are you exploring that negotiation through your interactions with your camera in hand?

Photography for me is both an active and an archival engagement with the land. I have always been driven to make pictures which exist within the landscape. For me land and photography are inseparably linked — photography that strives to be void of its spatial context lacks substance, and the act of photography plays a role in maintaining memory of the land and the lives which to which is bears witness. In South Africa in particular, land can be viewed as a signifier of the very complex social situation which is present there. Narratives which hold historical significance are all inextricably linked to who has control over the land and its resources. In South Africa, land is everything.

I have spent the past few years working as a photo assistant in the fashion industry, where I have been privy to the construction of images which are very much devoid of land and spacial context. Not that this is necessarily a negative thing — I find the idea of constructed fantasy within image making interesting — it’s just not the direction I am looking to go with my photography. I am interested in creating images with people who are in conversation with their surroundings.

Every interaction I have with the people I photograph is linked to the space we find ourselves in — it shapes the way we act and interact. At every moment we are negotiating our space — physically, culturally and temporally — and it is these negotiations I try to capture in my images.

When you begin a dialogue with the person you are photographing, how do you form questions that relate to discussing the immediate environment? Can you share some examples of how you would go about directing a conversation to focus on space.

It’s an organic process, and it varies from situation to situation. First, I’ll always introduce myself as a photographer and explain my intention to make pictures of aspects of the land and its people. I like to spend some time getting to know the people I am photographing, and if I can I’ll try to visit them on a few occasions in an environment they feel comfortable in. This allows me an opportunity to get a sense of them in their space. I wouldn’t say I consciously steer the person I am engaging into a dialogue about their immediate environment, but I’ve found that most of our narratives are so bound up in the physical environments we occupy and how we relate to them, that it naturally becomes a talking point.

What has been the most difficult part of your creative process? How have you worked to problem solve?

Something I try to be conscious of while making images is the question of authorship over people’s stories, which is so inherent in photography. Negotiating this discomfort is part of the very fabric of picture making, and is something which has yet to be solved in any real way. I’ve tried at various points in my career to actively approach story telling in different ways, such as giving cameras to people I am engaging with, dealing with ephemera and collaborating in creating photographs. More recently I try to embody these ideas subtly in the construction of my images through the degree of direction and interference, and the dialogue that exists outside the frame. I think it’s always something to be aware of when approaching people. I’ll often explain what drew me to them in the first place — the light, their outfit, some aspect of the scene. Historically, photography has been used as both a tool of liberation and subjugation (particularly in South Africa), so I feel it’s really important to be transparent about what I’m doing. There are often times I met with skepticism by potential subjects, and I always back off at the slightest hint of discomfort. It’s never worth pushing someone into making a picture they do not want to be involved in — these are not the kinds of pictures I want to make. Working with these issues is an ongoing process and part of negotiating what it means to act as a “documentarian” in other people’s lives.

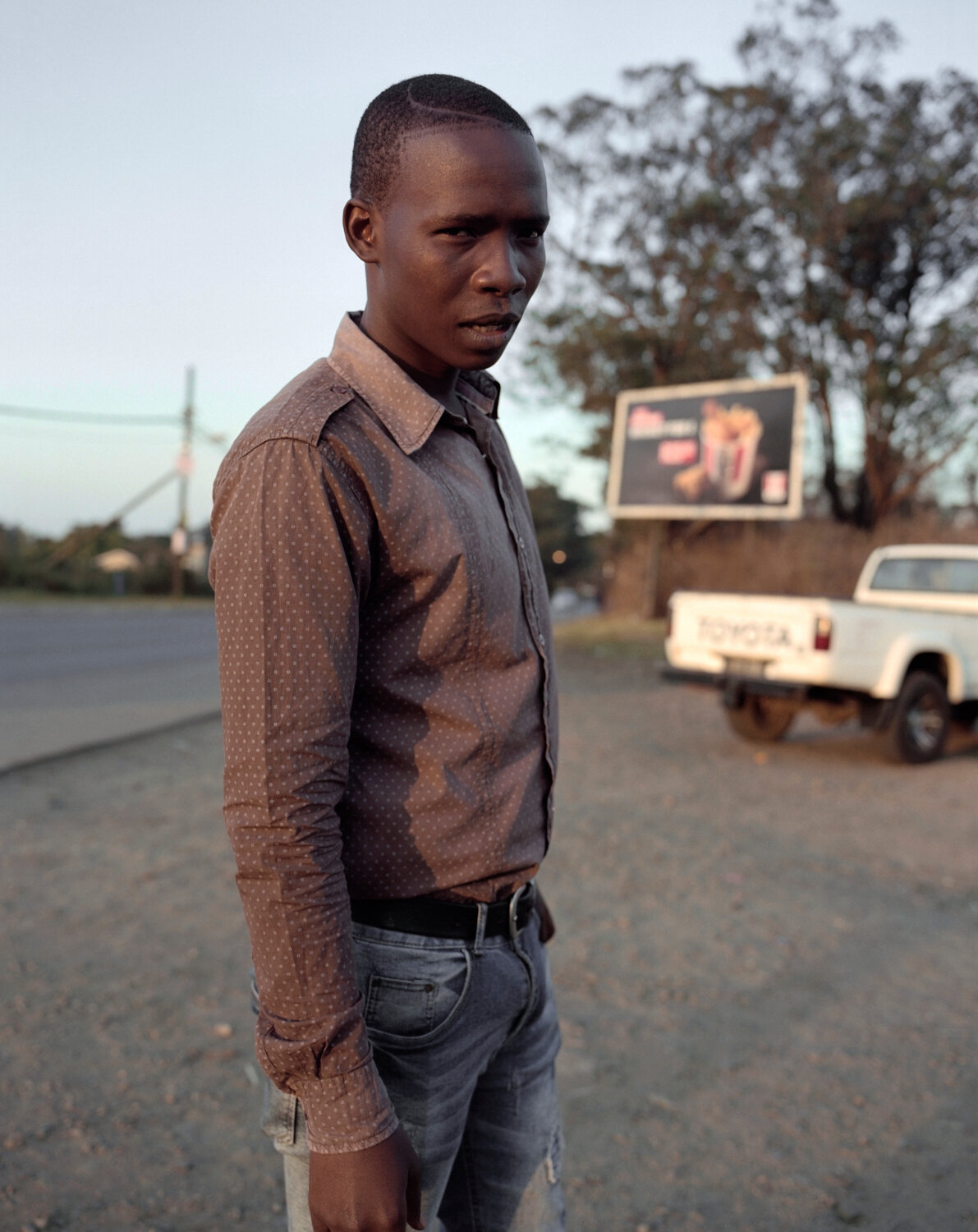

Dumisani and the neighbour’s dog, 2019

This is a portrait of Dumisani, the bodyguard to the mayor of Eshowe — a small leafy town in KwaZulu Natal in the heart of what was once the Zulu Kingdom. The town later became the administrative seat of power for the British in the 1800s. — a history that is still evident through its architecture and manicured flowerbeds, under canopies of indigenous trees.

I met Dumisani early one morning before his day shift began. When a neighbour’s motorised gate opened to allow a dated dark blue Mercedes Benz onto the street, with it bounded out a large dog. Dumisani and the dog seemed to already be well aquatinted.

To keep up to date with Robin Bernstein’s latest work, follow along here: