Iorgis Matyassy

Can you introduce us to your series ‘Ouagarasta’ what characteristics of this community peaked your interest towards diving deeper into discovering and exploring the Rastas in Ouagadougou?

Ouagarasta is a series of portraits of some people from the Rasta community of Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) and its surroundings. The young people who form the community, essentially composed of musicians and craftsman live from day to day by selling handicrafts, or any other activity related to tourism.

The idea was to photograph the people but also the environment they were living in, which was a mix between town and countryside... The characteristics that peaked my interest were mostly the fact that I felt close to these young people in a way, probably because of their rebel attitude. There was something about freedom in their way of being and they had this particular style that interested me… It's a community where everyone is trying to cultivate his own image. So I felt that taking these portraits was a good way to celebrate their image.

What have you learned about the Rastafarian beliefs?

I learnt different things about the Rastafarian beliefs, first of all that this is a religion without a dogma, so everyone has his own way of being Rasta. I realised the fact that this is really something about self, about the rules you choose to follow and by which you live your everyday life. But also in the context of Africa, this is something about the roots, about all these African cultures and its proudness that were destroyed by colonisation. This is a rebel culture where Che Guevara, Thomas Sankara (president of Burkina Faso from 1983 to 1987, who fought for the rights of the African nations, and against their economical dependency from former coloniser western countries. His government changed the name of the country from « Upper Volta », given by the French colonisers to « Burkina Faso » that means « country of the people with integrity »), Kwame Nkrumah, and other revolutionary figures are strongly venerated. A lot of the messages are going through the reggae music, especially with African artists like Alpha Blondy or Tiken Jah Fakoly both singing in French.

Faso was a horseman and a master of equestrian vaulting. When we went to meet him at his stables, it seemed obvious to portray him with a horse. When he brought the horse, I felt a really close relationship between him and the animal. The Horse has a huge role in Burkina-Faso, it is the symbol of the country. The Horse is part of the mythology of the birth of the Mossi kingdoms (that is the major ethnical group in Burkina-Faso).

In your project introduction you mention how the community of Ouagadougou interacts with tourism on a daily basis, is there anything in particular that you noticed about the constant exchange?

I was directly immersed into the community, because of friends (and my life partner at the time), who went there several times before me. So we were living with some of these people that I became friends with, but I didn't spend that much time with them when they were doing businesses. I can say that some of them were selling musical instruments that they were building themselves (as a lot of them were musicians), or different types of handcrafted jewelry. Some others were working as guides or any other activity that can make them a living. The constant exchange with tourists is the source of a living, it's a hard living, but in one of the poorest countries in the world, you have to find a way to survive, especially if you leave your family early like some of the Rastas did.

I can say that these constant exchanges with people from western countries make them discover a lot of things about our countries and cultures as we also do with theirs. This is something based on a mutual exchange.

I didn't see that much of the pros and cons of tourism in Ouagadougou. You don't have tons of people coming to Burkina Faso for holidays. Sure you have some, but a lot of people coming from western countries are working there for NGOs. This is not a major touristic destination, especially these days with the terrorist danger that you have in some parts of the country. This is a really poor country where people, when they have a job, live on something like 30€ a month!

In some cases we often find tourists focused on purchasing souvenirs from their destination rather than the opportunity for an exchange of dialogue with the person selling these goods, which in many ways creates a greater souvenir to return with. How did this project help you experience this community?

For me meeting these people through my friends whom they already knew, and through my photo project was a way to get close to them without having any material exchange (which I wouldn't do in this case anyway). I had already done some projects about urban communities in Europe, which I took with me and showed them. So they understood what I was looking for and what they were participating in by accepting to be photographed.

Maybe some tourists are missing this part of a trip, but I can understand that everybody is not looking for the same thing when travelling, and meeting others is also about giving from yourself as you say...

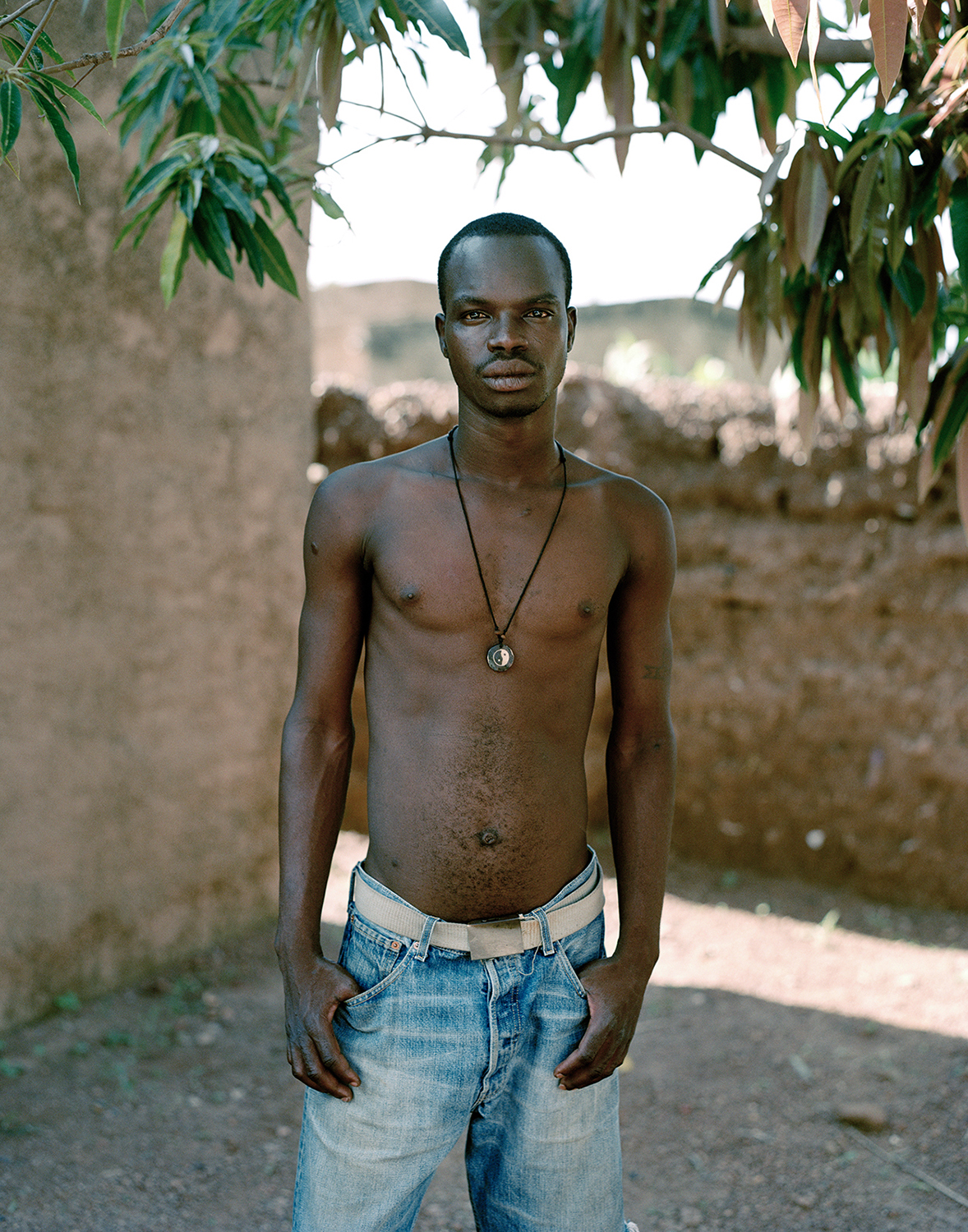

Salif was a member of the community of Sabaa (in the countryside), he was a musician, and lived there looking for a harmony with nature that he couldn't find in town.

Is there a sense of family within the Rastafarian community?

Of course there is a sense of family within the community, specially in the relationship between the younger and the older people, inspired by the relation between brothers in western African societies, where the younger has a due and a huge respect to the older often called « koro ». The younger members of a group are learning almost everything from the older about the Rasta lifestyle. This kind of structure often creates tensions between people, because they all want to have a better position.

All the people I've photographed are considering themselves Rastafarians, it's a philosophy that everyone refers to. It's mostly about being a free mind that isn't part of the « system ». It's about being an independent mind, especially in a traditional society where you grow up in a structure where often the group decides for you.

What did you give while creating this series and what did you receive?

While creating this series I've tried to explain honestly what I was looking for, then it was like with every other person I've photographed before: I was honoured that they have accepted, then I started to create a context in which I felt that they could incarnate themselves.

Can you elaborate on a moment while creating one of these portraits that greatly impacted you during this series? Or a conversation you had during working on this series that taught you or offered you new wisdom

I don't have any particular moment I can refer to right now, but of course meeting all these people offered me new wisdom, because alongside this work I became friend with some people and we spoke a lot. It was an impactful experience, because all these people had to grew up really quick, in a poor society, where they are facing life and death almost everyday. So being able to spend time with them, to share our experiences is something that makes you grow.

To keep up to date on Iorgis’ upcoming work follow along here: